No one remembers when the neighbors started calling the McCutcheons to complain about the loud singing from young John’s bedroom. It didn’t seem to do much good, though. For, after a shaky, lopsided battle between piano lessons and baseball (he was a mediocre pianist and an all-star catcher), he had “found his voice” thanks to a cheap mail-order guitar and a used book of chords.

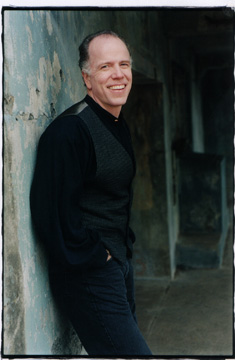

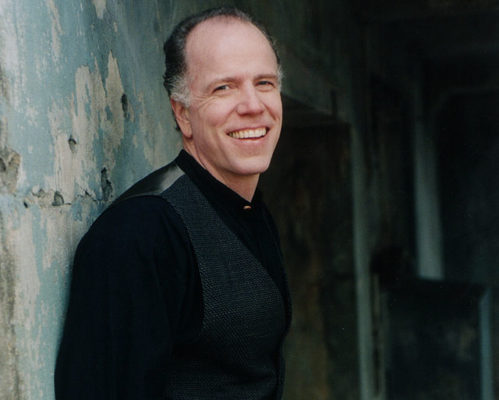

From such inauspicious beginnings, John McCutcheon has emerged as one of our most respected and loved folksingers. As an instrumentalist, he is a master of a dozen different traditional instruments, most notably the rare and beautiful hammer dulcimer. Critics and singers around the globe have hailed his songwriting. His recordings have garnered every imaginable honor, including five Grammy nominations. He has produced over twenty albums of other artists, from traditional fiddlers to contemporary singer-songwriters to educational and documentary works. His books and instructional materials have introduced budding players to the joys of their own musicality. And his commitment to grassroots political organizations has put him on the front lines of many of the issues important to communities and workers.

Even before graduating summa cum laude from Minnesota’s St. John’s University, this Wisconsin native literally “headed for the hills,” forgoing a college lecture hall for the classroom of the eastern Kentucky coal camps, union halls, country churches, and square dance halls. His apprenticeship to many of the legendary figures of Appalachian music imbedded not only a love of homemade music, but also a sense of community and rootedness. The result is music – whether traditional or from his huge catalog of original songs – with the profound mark of place, family, and strength. It also created a storytelling style that has been compared to Will Rogers and Garrison Keillor.

The Washington Post described John as “Virginia’s Rustic Renaissance Man,” a moniker flawed only by its understatement. “Calling John McCutcheon a ‘folksinger’ is like saying Deion Sanders is just a football player…” (Dallas Morning News). Besides his usual circuit of major concert halls and theaters, John is equally at home in an elementary school auditorium, a festival stage or at a farm rally. He launched the first-ever joint tour of a Russian and an American folksinger with 1991’s US-USSR Friendship Tour, playing to packed houses in both countries. The past several years have seen him headline five different festivals in Australia, tour Nicaragua on behalf of a children’s literacy program, record four albums of songs and music, perform in the first-ever children’s concert on the Nashville Network, give a featured concert at the AFL/CIO Convention, author a second songbook and a children’s book, score four videos, talk about songwriting with children on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, produce three recordings to benefit a community organizing group, garner five Grammy nominations, and debut his work with symphony orchestras.

But it is in live performance that John feels most at home. It is what has brought his music into the lives and homes of one of the broadest audiences any folk musician has ever enjoyed. People of every generation and background seem to feel at home in a concert hall when John McCutcheon takes the stage, with what critics describe as “little feats of magic,” “breathtaking in their ease and grace. . .,” and “like a conversation with an illuminating old friend.” After sharing the bill with him at several shows, Johnny Cash was so impressed with McCutcheon live performances that he had John perform at his daughter Roseanne’s wedding. While introducing McCutcheon to a wedding group including people like Ricky Skaggs and Chet Atkins Cash commented, “This is just the most impressive instrumentalist I’ve ever heard.”

John released The Greatest Story Never Told on Red House in 2002 to rave reviews. The album reflects on the past and recognizes that we can no longer live there, and that each one of us must strive to live up to the legacy left by preceding generations.